Sunlinesamoa (20 April 2023), Note from the UK Foreign Office, Britain’s Foreign Secretary, and the fair question, “Why would a veteran politician [the Foreign Secretary] mistake our Prime Minister for President”? An honest mistake, a literary error, or an innocent slip of the tongue?

Whereas theories and hypotheses are not normally constructed on the basis of or confirmed by a single reference, we should not shut our eyes to what has been happening in Samoa right before those very same eyes.

This Reminder is for Us, not the Foreign Secretary of another Commonwealth nation. It is for We the People of Samoa, and the written Records of Samoa’s constitutional history and jurisprudence.

Samoa is not Federal America & We do not have a president

On the 21st of September 1960, the Constitutional Convention 1960 expressly rejected a Motion from the floor that `the Head of State should be known as the Chief Executive of Western Samoa.’ (Records of the Constitutional Convention Debates 1960, Volume I, 421; italics added)

If the Motion were accepted, Samoa would have followed the American presidential system. Was the Motion rejected? YES, most certainly!

In response to the proposal that the Head of State of Samoa be given a power of veto of parliamentary legislation like that of the US President, Professor James W. Davidson (constitutional law advisor to the Constitutional Convention 1960) pointedly reminded the Convention of our Westminster pedigree:

This would be a very good proposal, if it was intended to give the Head of State similar powers to that of the President … who is of course the Head of the Executive Government.

That means that the President … has, in effect, the powers that we are conferring on the Head of State and also the powers we are conferring on the Prime Minister [of Samoa].

That is the American President is completely involved in politics, and it is accepted that he expresses an opinion and takes decisions of a controversial character on matters of government policy.

In this Constitution, however, we are following a system similar to that followed in Great Britain and New Zealand and many other countries of the British Commonwealth, where the Head of State is regarded as being above politics and outside them and not a person who takes sides in political matters.

(Records of the Constitutional Convention Debates 1960,

Volume II, 425, 846; Volume I, 421; italics added)

Standing up `for the unity of the whole country,’ the Head of State should not be concerned with `matters of controversy’; and shielded against partisan politics, `it is the responsibility of the Head of State to act as trustee for parliament and for the whole country in order to see that everything is carried out in a lawful and correct way.’ (Records of the Constitutional Convention Debates 1960, Vol.I, 846, 425)

Samoa is Westminster “with little modification”

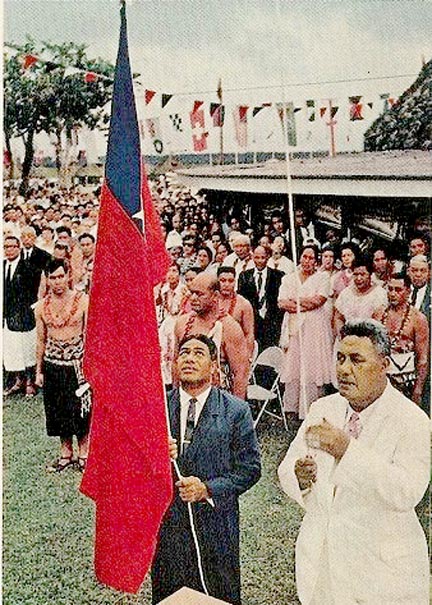

Joint holder of the Head of State position, le Susuga Malietoa Tanumāfili II, in his Address on the Opening of the Parliament of Samoa during the first Independence celebration in January 1962, was unequivocal regarding the system of government Samoa has adopted:

By our Constitution, we have adopted with little modification the system of Parliamentary Government evolved among the English people. (Parliamentary Library, Samoa, 1962; italics added)

Since the words “little modification” are not written upon the text of Samoa’s Constitution 1960, it is every Samoan’s responsibility to:

(1) find out what the “little modification” was and is; and

(2) determine, as far as possible, the intersection between Samoa’s written Constitution 1960 and Westminster’s constitutional matrix of conventions, reserve and prerogative powers, institutions, constitutional values and so on, whether or not those are already coded in the text of Samoa’s Constitution, and what the importance of such coding or non-coding is.

Samoa is a Constitutional Democracy, not a Constitutional Monarchy as in England

Restricting the eligibility for the office of Head of State to the Tama a Aiga, and incorporating that in the body of the Constitution 1960, was understandably an extremely controversial issue in the Constitutional Convention 1960.

It took more than four days in September for the Convention to finalize the issue. Unsurprisingly, the debate was very heated and long. (Records of the Constitutional Convention Debates 1960, Volume I, 247-267)

Professor Davidson was very clear on the issue:

The Working Committee had an important reason for dealing with this matter by Resolution rather than including it in the Constitution. Anything that goes in the written Constitution is to be interpreted by the Supreme Court.

The position and the dignitary of the Tama-Aiga is a matter that relates to Samoan custom …

[A]ny dispute that might arise in regard to the Head of State would be settled by the Legislative Assembly itself, which consists of the representatives of the Matais, and not settled by the Supreme Court, as it would have to be if it was written into Article 18. (Records of the Constitutional Convention Debates 1960, Volume I, 243, 307)

One delegate wanted only one Head of State. His preference betrayed his socio-cultural bias. Another wanted the joint-holding of the office of Head of State (under the repealed Article 17 of the Constitution 1960) to `continue until the end of the world,’ and that henceforth there should be only two officeholders, one each `from the two families of Malietoa and Tupua.’

What about other Tamas? Could there be any Tamas without Aigas? And what about other Aigas, Aiga o Nofo, Aiga o Papā, Aiga Tafa’ifā, Aiga o Tupu? Those questions went to the very heart of our Samoa’s social culture. Then with the maxim of “thinking in a Godly way” from le Tofā Auelua Filipo, the issue was thoroughly divinized and the motion was accepted on the voices.

In 1960, the Convention decided in favour of the joint tenure for the office of Head of State, le Susuga Malietoa Tanumāfili II and le Afioga Tupua Tamasese Mea’ole, and let the Legislative Assemblies of tomorrow deal with tomorrow. That would be their role in Samoa’s constitutional democracy.

That was also the decision of the Constitutional Convention 1954, presented to the Convention 1960 as a Recommendation. `Future vacancies in the position of Head of State should be filled in a way to be decided by the Parliament of Western Samoa when the time comes.’ (Records of the Constitutional Convention 1954)

In England, succession to the English royal throne is hereditary, something about a royal line. Although the Westminster Parliament endorses the next Monarch, he/she should be from within the royal family itself. After the late Queen Elizabeth II, then her son King Charles III, and after him, his son and then others down the so-called royal family line. This is all part of their English constitutional monarchy structure, rooted in English history, custom and tradition.

Not so in Samoa. While the Head of State is elected by Parliament, who the Tama a Aiga are at any given point in time is a matter for the Aiga themselves to decide – not Parliament or the Court.

The Convention 1960 thus wisely left the election of a Tama a Aiga as the Head of State of Samoa (or, for that matter, as the Prime Minister of Samoa) outside the purview of the Constitution 1960. Being a matter of “Samoan custom”, the Convention wisely placed the matter of Tama a Aiga outside the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. It would have been otherwise “if it was written into Article 18.”

My point is, first, the rejection of the American presidential system by the Constitutional Convention 1960 has important ramifications and implications for Samoa’s Parliament, Executive Government, and Judiciary. These matters, and their descriptive and normative justifications, must be properly ascertained, articulated, and followed.

Secondly, the Executive Government and/or Parliament and/or the Judiciary could not, and should not either unilaterally or jointly howsoever change Samoa’s mandated system of government without the knowledge and democratic will and voice of We the People of Samoa.

Thirdly, ex hypothesi, the Constitutional Convention 1960 did not create the office of Head of State of Samoa while secretly envisaging its future destruction as a fait accompli. The Convention wisely and knowingly invested the Head of State with sufficient substantive and procedural powers, undergirded by constitutional principles and democratic values, to fulfill his “actual duties” under the Constitution 1960. (Records of the Constitutional Convention Debates 1960, Volume I, 242; italics added).

The Head of State must “constantly be making certain that the work of the Government is carried on in accordance with the law, in an unselfish spirit, and in accord with the conscience of those who are doing the work of Government.” And, “he will have the responsibility of ensuring that, no matter what emergency, the work of the Government is carried on smoothly in the interests of the people.” For all that, as “the most dignified and important position in the Government,” the Head of State of Samoa “must have the respect of everyone.”

Finally, in light of what is still going on since 2021, we pray more fervently for peace in our beloved Samoa. Peace, so they say, starts in a human heart that has found peace with God, with others, and with itself.

Or should we – like Nero playing “fiddling politics” while Rome was burning – keep on digging when Samoa is already in a very big hole?

Ua si’i fale. Ua si’i matālālāga. Ua si’i tā. O le tai o I’a, o upu e fai i Tautai mata palapala, le tū a le masina, o le māunu a le apogāleveleve, ma le popo masa tafetafea solo. A fa’atamasoāli’i, seu va’ai.

E se’e mālie i’a o le loloto, ae fetaia’i fa’alamāῑse i’a o le papa’u. Manatua, o Samoa e lē se’u fulu. Le upega ua toe masaesae lava ona o le mana’o, le fa’asanosano, ma le laumei na te toe va’o lana lava fanau.

Dr Iutisone Salevao

(Academic lawyer, researcher, and author)

AUSTRALIA